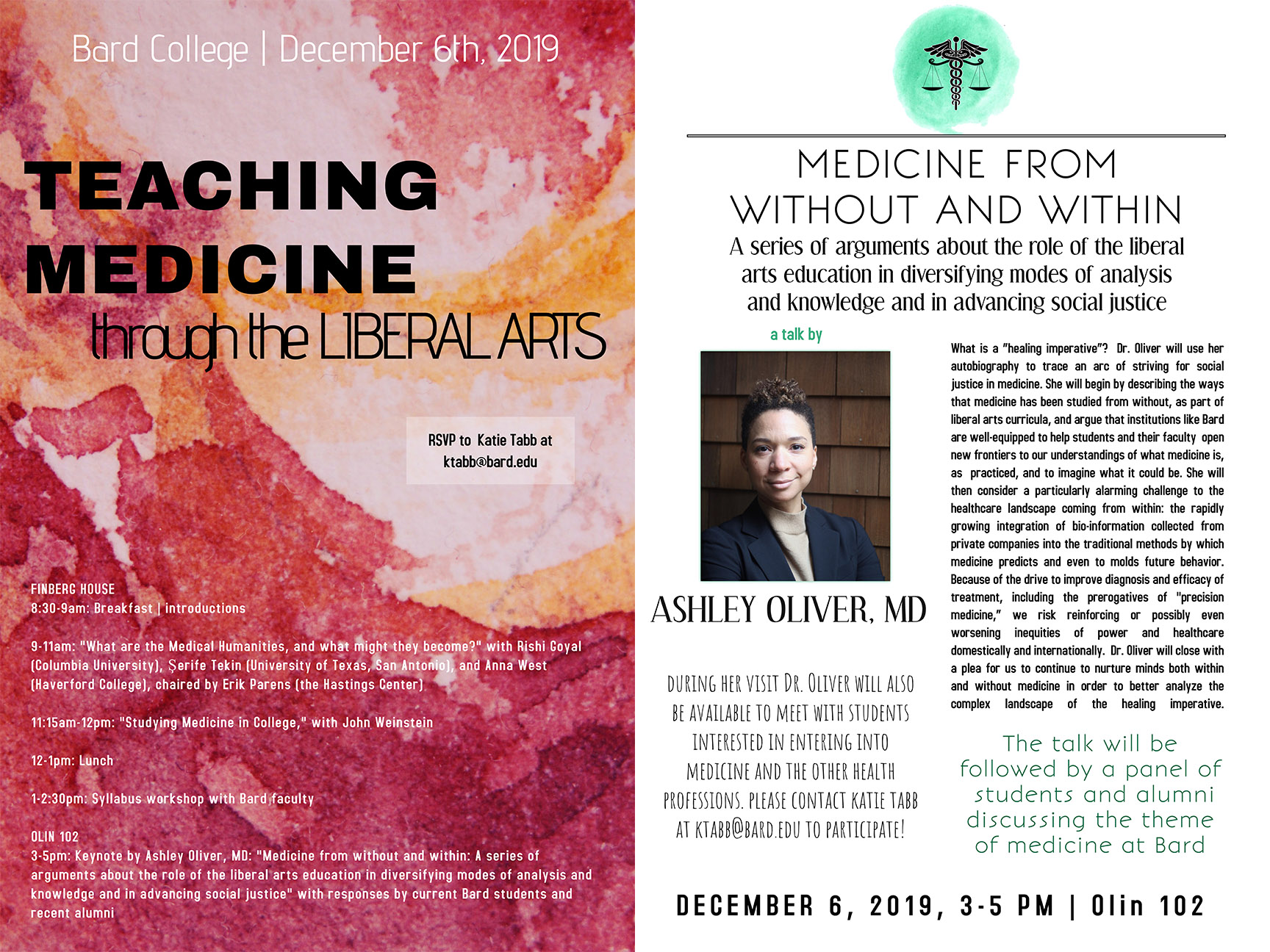

We are very pleased to share Dr. Ashley Oliver’s timely and compelling keynote lecture from Bard College’s “Teaching Medicine through the Liberal Arts” conference, “Medicine from without and within: A series of arguments about the role of the liberal arts education in diversifying modes of analysis from within medicine and in advancing social justice.” Read the full keynote below.

Welcome: Greeting and gratitude

Hello, welcome, thank you for spending your time with me. Honored to be here.

Before we dive in, I will walk through the rough outline of where I would love us to journey together over the next hour. I would love to dedicate the end of our time together for dialogue.

I’ll start by giving you a sense of who I am. I’ll do this by sharing the stories of my own parents. As I hope to show, I am shaped by them. Specifically, (1) my parents’ own values of critical inquiry; (2) political frameworks like the anti-slavery and the Civil Rights’ Movement, women’s liberation/feminist critique; and (3) spiritual lattice that is Jewish in original orientation but ecumenical in practice. These analytical, political and spiritual frameworks are the basis for a healing imperative. These frameworks would go on to shape my orientation as an undergraduate, in graduate and medical school, and now as a resident in the Anesthesia Department at the University of California, San Francisco. I’ll call my orientation a “healing imperative” and I’ll try to illustrate how it arises from the synergy of direct political action, academic/intellectual analysis, and ultimately, a component of spiritual humility that I will describe as the work of care.

My description of a healing imperative is something still very much in development, but has these three components. In my narrative I will try to show how background like my liberal arts education, experiences in community organizing and direct political action, and even an emerging spiritual framework about what it means to be a human and to work in a care giving field, converge.

To get to my definition of a healing imperative, I invite you to trace my journey from undergraduate life, to medical school to residency. As an undergrad, I studied politically charged documentary film and engaged in direct political action and I was involved in community organizing projects on Chicago’s segregated South Side. This organizing work grew from ongoing work against immanent domain of the University on the South Side of Chicago, which we saw as a necessary counterpoint to our privileged position in the Ivory Tower.

The middle chapter of my arc takes place in the liminal space of graduate school and into medical school. While as a graduate student at UC Berkeley, activism and critical inquiry seemed difficult to integrate, once I was in medical school, my involvement in White Coats 4 Black Lives became a natural focus point that would allow me to do both. It was as a medical student that I began to better articulate how public policy, public health, structural racism, violence against Black and Brown bodies, microaggressions and social hostility, all converged in the crisis of worse health outcomes for vulnerable populations.

Finally, I’ll give you a sense of my current interests/projects. As a resident physician, the core of my job is focused on learning how to take care of patients. From a reductionist perspective, this entails improving my ability to diagnose and treat patients. But I will try to argue that learning how to give care is a deep social and even spiritual process, that is poorly described and under-appreciated in medical training. Acknowledging this is the first step toward a more holistic, human-focused, healing imperative. Although we won’t have time to fully untangle this today, I think this final component—the component of care—will be what defines excellent medicine in the future. I believe it will become an important battle place to define what makes our work human-focused in a world moving quickly to automation, big data, machine intelligence.

Part One: Who I am

The odyssey of departing from and returning home is a familiar one, [1] as is the lesson that one never returns home the same person that one departed as. My story begins in a household of physicians and ends up with me now: the head of a household as a physician. My path to physician-hood, despite my parenting, was anything but straightforward.

My father was born in Wilmington Delaware in 1944. My father and his sister, a historian, have talked about “growing up in a reading household.” Politically, this was important, and through lessons that my father taught me in early childhood, I connected reading and learning with the emancipation from slavery. Academic achievement was a part of the dominant orientation in the home that my father grew up in.

My father inherited his parents’ drive for academic achievement. He learned about a public high school program to attract students of New Haven’s Hill House High School to Yale University (honestly, a college none of his peers or neighbors in Wilmington, DE had ever heard talk of). He set himself off to live with his own grandparents, who lived in downtown New Haven, and in fact matriculated to Yale in 1963. By the measures of his community and social class, he had achieved the unthinkable.

At Yale, my father majored History, Arts and Letters. His undergraduate thesis was on William James’s theories of the self. He followed his undergraduate studies with a Master’s in Divinity. He told me recently in conversation that his desire to become a physician was “in an effort to understand the healing of mind, spirit and body.” This would complete the arc, having devoted himself to the life of the mind as an undergraduate, and to the life of the spirit in divinity school.

My mother was the daughter of a periodontist and educated housewife. Shaped by her own experienced of the death of her younger brother to an osteosarcoma the year after his Bar Mitzvah, she later once to me that she knew if she didn’t become a physician, she knew “at the end of [her] life [she] would regret it.” A philosophy major as an undergraduate, my mother stayed at the University of Washington for her post-baccalaureate premedical courses. She applied to medical school three times, battling the prevailing sentiment at the time that men were superior applicants to women and weathering comments by programs about not wanting to “waste a spot” on a woman whose career and earning power was regarded as diminutive to a man’s. My mother still recalls the name of the secretary at Tufts Medical school who advocated for her, taking her off the waiting list. It was there where my mother eventually met, studied with, and married my father.

I grew up in a house of literature. Medical texts and journals but also Jane Austin, Dickens, Homer, James Joyce. The classics of sociology: Milton, Singer. Of philosophy: Kant and Hegel. Of science of the mind: Jung and Freud, Eric Erikson. Postmodern theorists like Franz Fanon, and feminist and womanist thinkers like Simone de Beauvoir and Sojourner Truth were names I knew at an early age. Overall, the values of learning and inquiry were foundational. It would make sense that when picking a college, I would look to an institution committed to the “life of the mind.”

Interrogate the world, was a central lesson I learned.

Another was: engage in community.

A third was: help people.

Part Two: Without to Within: Tracing a healing imperative on the road to medicine

Medicine from without: Public health and social justice on Chicago’s South Side as an undergraduate

I found a ready intellectual home at The University of Chicago. It’s promise of “the life of the mind” guaranteed to me that I would spend four years engaged in critical debate. And although I was passionate about academia, Chicago held another promise for me which a came to discover. Because I inherited from my father a Black American anti-slavery and Civil Rights’ narrative that demanded political engagement, and because I inherited from my mother the Jewish values of Tikun Olam or, repairing the world, during these years I also began to develop as a political activist. This political work would become important to grounding relevant academic discourse. Outside of school, my peers and I set about to address the history of immanent domain of the University on the South Side of Chicago. It was during this time that I first experienced the work of community building and community organizing. My peers and I founded a tenant’s rights organization that is still in existence today.

When it came time to write a thesis, I aimed to balance both. My thesis described the production and circulation of an independent Chicago film, The Chicago Maternity Center Story, (Kartemquin Films, 1972). Although the paper primarily investigated the film as documentary within a public sphere, I also drew on history and medical anthropology in order to contextualize the debates about public health, maternal health, anxieties of health care disparities, of big pharma and hospital consolidation, and the feminist movements of that time.

The documentary, in chronicling the threat to the maternal health center and its ultimate demise, was intended to be (and was), a site where community members and “city residents could be empowered to identify and challenge the power relations that shaped the environmental and social conditions that affected their life chances.” [2] Community health centers, like the Chicago Maternity Center understood personal and community well-being as necessarily part of political and economic movements toward liberation. Community health was the product of a “social and physical environment… reflecting a long tradition in social medicine, [which] in the US certainly dat[es] back to the public health movement of the mid 1800s. [Community health centers] took [their discourse] in a more radical direction by calling for the political education of their patients, and the revolutionary transformation of American capitalism.” [3]

This was work that built explicitly on preexisting anti-slavery, civil rights, and anti-colonial movements and was enacted by Black and Brown community members who saw free medical care “as a means of decolonization that would bring about social justice, self-liberation, and self-determination.” [4] For example, as articulated by a member of The Young Lords at the time “a free health center [is both] a dire need and… [is also] a revolutionary organizing tool… We now see the health center as a survival program to aid our community in their 24 hour a day struggle to survive.” [5] These arguments had been articulated by groups like the Black Panthers [6] and the feminist movement via documentaries like The Chicago Maternity Center Story.

Here was the first layer of a healing imperative, which took root standing from outside of medicine, through academic work I did on documentary film about community health centers, along with the direct political activism of community. I learned about the historical critiques of medicine: how modern western medicine privileged some voices and bodies over others. I learned about the long-standing efforts that women, and black and brown community members had launched to gain authority over their health and their conditions of existence.

Medicine from the liminal place: Social justice in medical school

Organizing work, intercalated with academic inquiry, followed me through graduate studies in Berkeley, California, and back to the East Coast, where I turned my attention to discourses of land sovereignty, food politics, and diet, ecology/climate justice, and global health. While my mind was busy working through these connections, my hands were busy learning how to farm and work in kitchens. (I might have been working out my own trinity of “mind, body, and spirit” that my father had sought out decades earlier.) Eventually, as with my parents, medicine beckoned. I finally understood that through medicine I could continue to apply critical inquiry to social justice work and vice versa. And I finally understood that my urge to be involved in improving the health and lives of communities were an expression of Tikun Olam.

Although outrage with police brutality had been simmering since at least 2009 and the murder of Oscar Grant, in 2014, a new urgency was felt by me and my peers, to be engaged in work that addressed this. In the wake of first wave of the Black Lives Matter movement, White Coats 4 Black Lives was launched simultaneously in cities scattered across the US with academic medical centers. This was led primarily by undergraduate medical students, although the aim was to organize the medical community broadly. It’s first action was a national die-in featuring approx 80 medical schools and involving 3,000 students.

This die-in sparked campus conversations, spurred workshops, and engaged students who previously didn’t see how questions of diversity implicated them. At Columbia, our work involved the medical school the residency programs, medical faculty and our administrators.

We saw our work as stemming directly from the community focused health care movements of the 1960s and 1970s, which argued that health care was a fundamental human right, and that universal health care would never be plausible without reformation of late capitalism, deconstruction of structural racism, and the redistribution of voice and power in the clinical context.

Our mission included:

- Encouraging physicians and medical institutions to publicly acknowledge racism as a public health issue

- Promoting medical students to stay involved in local and national movements aimed at ending racism and police brutality

- Advocating for research on the adverse health effects of racism

- Advocating for the establishment of a single-payer national health insurance program

- Improving the recruitment and support of Black, Latinx, and Native American medical students, as well as faculty of medicine

- The development of national medical school curricular standards that educate medical professionals on the history and current manifestations of racism in medicine, principles of anti-racism

- Participate in the strategies of dismantling structural racism

Like critiques of health and society by the Civil Rights movement/Black Panthers, The Young Lords, and second wave feminism health disparities were cited as originating in larger structural inequities and refracted by capitalism. This work is far from finished: ongoing questions include how do we continue to dismantle racist structures in medicine and society? How can we continue to recruit, support, and retain robust and diverse practitioners? How will economic structures continue to disadvantage poorer populations and what will we do about it?

Medicine from within: defining care using a healing imperative (or: the vexed task of care)

The final thread to weave into my healing imperative is a newer dimension that I’ve begun to explore. This is the social-relational or even spiritual dimension of caring work. In his latest book, The Soul of care: the moral education of husband and doctor, Arthur Kleinman describes care decades into practicing as a physician as a deep, almost spiritual process that in anthropological terms.

“Care is a human development process… Care is centered in relationships. Caregiving and receiving is a gift-sharing process in which we give and receive attention, affirmation, practical assistance, emotional support, moral solidarity, and abiding meaning that is complicated and incomplete… Caregiving entails moments of terror and panic, of self-doubt and hopelessness – but also moments of deep human connection, of honesty and revelation, of purpose and gratification.” As Kleinman readily admits, “the domain of caregiving extends beyond the boundaries of medicine.” [7]

Care is a relational and spiritual process that I learn about through millions of small experiences that unfold over an hour, a day, a week, a month. I derive my care experiences from my training as an anesthesiologist, as a wife and mother, and as a friend and colleague. Anthropology can help me to a certain extent untangle what care means, but ultimately, I rely on my evolving spiritual work to guide me in refining what care could or should look like.

Within a healing imperative, care can help us ground a political and social context for medicine. It can lead us to produce thoughtful analyses about the challenges in treating vulnerable populations like the global poor, the non-literate, the differently abled, geriatrics and children. A care practice is necessary for physicians in order to ward off burnout and professional despair, especially during a time where clinical knowledge and expertise is exploding under the banners of machine learning, artificial intelligence and precision medicine. Care is as much political as it is social, as it requires the intimacy of two parties in an exchange relationship.

Care in medicine is always already challenged. The work of care in medicine is difficult to quantify, analyze and as health care companies will tell you, very challenging to reimburse. The future of what care will be in medicine is not clear. Some authors like Dr. Eric Topol suggest that machine learning, technology and artificial intelligence will remove the automatable and possibly more grueling elements of practicing medicine by outsourcing to machines, leaving care for our human to human interactions. Other authors worry that with precision medicine, artificial intelligence, the automation of medicine through machine learning, that our work will become de-humanized, more automated. My background in cinema and media studies leads me to believe that any new technology simultaneously brings us new challenges and new advantages. I believe we will continue to learn how to care for one another now, as we have done for centuries.

Conclusion: the only way out is through (critical inquiry)

Production of knowledge beyond just biologic.

Commitment to social justice and global health.

Making space for a spiritual dimension in medicine to decrease burnout and increase meaning derived from work.

I have tried, in this talk, to demonstrate through my own narrative path what a healing imperative could look like. It is a healing practice that is grounded in but in no way is exclusive to medicine. It must rely on contributions from humanist and social science thought traditions.

This healing imperative is a multi-modal approach that I hope will support a lifelong career. It is necessarily interdisciplinary. Critical inquiry must produce more than just biologic knowledge. It relies on both Geisteswissenschaft and Naturwissenschaft. It must amenable to community-based perspectives and must be environmental and global in scope as well. It must acknowledge legacies of trauma, inequity and exploitation. It should support the health and vitality of the medical trainee, the health care worker, and our partners in allied health professions. It requires acknowledgment of the spiritual dimensions of suffering and illness, and that not all health care is oriented toward cure or remission.

How can a healing imperative be useful? It can inform our future work on medical ethics. It can help us rewrite new social contracts around patient autonomy, the doctor-patient relationship, and new anxieties around Big Data, machine learning, artificial intelligence, and health data privacy. It can ground global health work and help us narrow the gap of health disparities. It can help us improve diversity in the health care workforce. It can improve health care. It can contribute meaningfully to how we choose to include ecological and climate justice concerns in the next chapter of medicine that we write.

As a physician, I’m committed to a healing imperative that can be applied to my profession of choice. It is my duty not only to care for myself, my patients, and my colleagues, but also to care for and be a steward for my profession. My commitment to thinking through and helping share a future for human medicine derives from work I have done in my previous lives as a historian and human science scholar, my work as a community activist, and my role as a mother, partner and resident. The way I express my care of the field of medicine is by taking time for critical inquiry of it: this process is deeply indebted to my training in the liberal arts. In the critical inquiry of medicine, I welcome (and hopefully solicit!) partnership to make medicine better for all people, not just the most privileged. I am so humbled to have been asked to share my thoughts with you, and hope we can spend some time in dialogue to think through ways forward, together.

[1] Campbell, Joseph. Hero with a thousand faces: Second Edition. Princeton University Press: 1968.

[2] Jerome, Jessica. Much More than a Clinic: Chicago’s Free Health Centers 1968-1972, Medical Anthropology, 38:6, 537-550, 11 Jul 2019. DOI: 10.1080/01459740.2019.1633641

[3] Jerome 544.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Nelson, Alondra. Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight against Medical Discrimination. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

[7] Kleinman, Arthur. The soul of care: the moral education of a husband and doctor. New York: Penguin/Viking. 2019.